Where Is the Weak Link?

Do you think about weights when rigging, or just tie stuff on and proceed to cutting? Are you someone who spends time factoring in angles, vectors and the system that needs to be built for the task ahead, or are you just throwing a rope up there and hoping for the best? When’s the last time you devoted some time to inspecting your rigging equipment? Have you thought about, if something were to go wrong, where the failure might happen? Well, for those reasons and many more, this article is aimed at addressing these thoughts.

Why do we rig?

We opt to rig for multiple reasons, but often I find that arborists don’t always devote the same amount of attention to the rigging as they do the climbing or the equipment.

So why do we rig? Ask yourself that. Why do we deploy rigging systems to conduct our work?

The immediate response is likely something to the tune of, “The space below doesn’t allow for us to free fall the debris.” Another common answer is, “To improve the flow of a job site.”

Making it rain brush and wood is fun and all, but the cleanup can be the thing of nightmares. I still recall the projects where I spent more time with a rake than I did with my saw and harness, desperately wishing I could go back and do the project over.

That’s not how tree work happens, though. We choose to do something and then operate inside the consequences, both good and bad, applying what we learn in the process to the projects ahead. Maybe, though, you utilize rigging because you invested thousands of dollars in equipment and want to use it, whether it be for your own satisfaction or for more likes on Instagram.

The point being, we make a conscious decision by utilizing ropes to assist in the removal of debris from the trees we work on, and we need to be intentional with our approach to the rigging operation.

Weak link

The title of this article is about identifying the weak link in your rigging system. Do you know what yours is? Immediately, when I wanted to write about this, I thought in terms of the components themselves. The trees, ropes and equipment. Basically, what we directly work with. What we touch.

As I thought about this topic more, however, it dawned on me that the weak link may be knowledge of and confidence in what we are doing. We’re going to talk about equipment for sure, but this can only go as far as your knowledge and creativity allow you to use that stuff to do these things.

We need to make sure we are thinking about what we are working with and consider the limitations. The Green Log Weight Chart is a powerful tool, and there are even a few different versions of an app that makes estimating weights easier than ever. I’ve used the Log Weight Pro App for many years now, and it’s great. It doesn’t have an exhaustive list of species, but there are more available than what’s on the paper copy of the log chart. Whether it’s crane work or just estimating weights for day-to-day rigging, it’s a very important tool.

Why does weight matter?

Free ads aside, why does the weight matter? During training and seminars, we speak a lot about the working load limit (WLL) of equipment as it compares to the minimum breaking strength (MBS). MBS meaning, when something is brand new, with what force would the rope or equipment break with a constant pull? To determine WLL, we take the MBS and reduce it using a 5:1 ratio (10:1 in climbing), to preserve the strength of the equipment and ensure it’s around for as long as possible.

When you hear “cycles to failure,” think of the number of times a task is repeated over and over until the equipment decides it’s had enough and finally breaks. This is why the MBS:WLL is roughly a 5:1 ratio, to ensure we get the most cycles out of a piece of equipment before it fails, with the goal being it never actually gets to that point. That instead we retire it from service before something fails, rather than continue to use it until it fails in the middle of the job.

Equipment and knowledge

We spend a great deal of time, or at least we should, inspecting our climbing and aerial-lift equipment. It is something that is wildly important to keep us safe and sound while we are trusting our lives to this equipment. Do you devote that same time and energy to inspecting and familiarizing yourself with your rigging equipment?

Many times, we as arborists tend to look at our rigging equipment with a bit more casual attitude. “Yeah, that rope is kinda glazed, but it’ll hold for a bit longer. That rigging sling has a few knicks in it, but it’ll be fine. The port-a-wrap has a groove that’s been there for a while, and it’s awfully shiny now. I wonder if it’s time to replace it.”

Maybe that’s not your normal, and if so, kudos. But if any of that sounds all too close to home, this is why I’m writing the article. We need to think about where our weak points are in a system and design a plan around them to make sure the weakest parts are as strong as possible.

With that in mind, when you read about identifying the weakest link, what do you think about? If it’s your knowledge, there are plenty of ways to increase that. Whether it be specific classes and training or found in books like “The Art and Science of Practical Rigging” (by Peter S. Donzelli, Sharon J. Lilly, ISA), there’s a lot out there these days to help increase your knowledge and think about things differently.

Identifying the weak link

When it comes to the actual execution, though, how about the components? If I’m looking at a tree that is to be worked on, I think about three things: the tree, the equipment and the space.

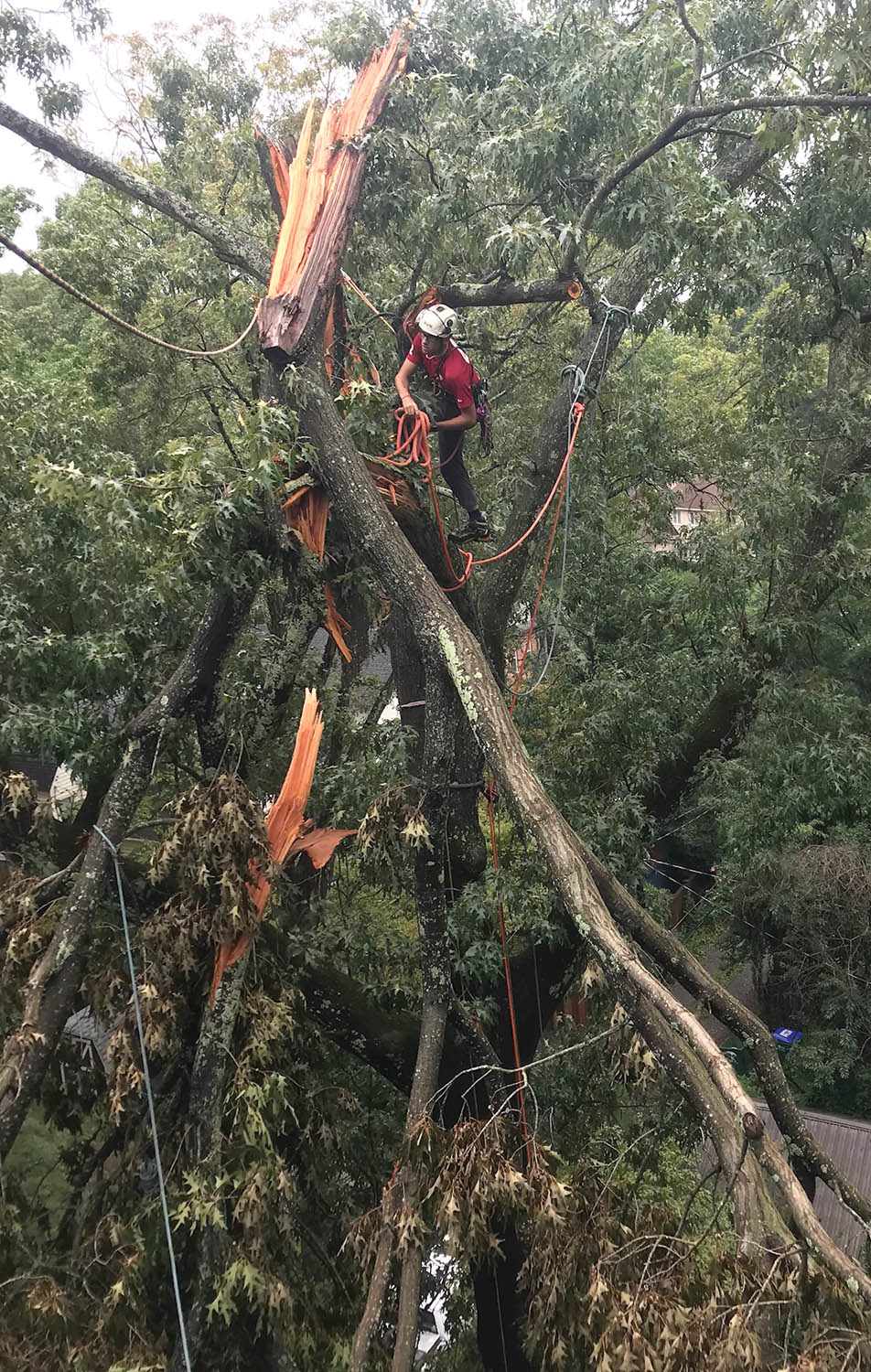

When it comes to building a rigging system for the task ahead, identifying the weakest point of our system is essential. The tree should not be the weakest part, as much as we can help it. Sometimes, the nature of what we are working with is limiting. Whether it be the diameter of the wood, the species and/or some level of decay, we may find a time when the tree is the weakest component in the system. Regardless, we as the technicians aloft have to account for that and mind the weights and forces as much as possible.

Using additional blocks

In many cases, I’ll use additional blocks to change how the applied force can be spread out through the geometry of the tree. I’m trying to add compression into unions, and designing a system to load the tree to work with the grain as opposed to against it. Imagine breaking a pencil. Do you do so by pushing it from end to end vertically? Or do you flip it horizontally, put your thumbs in the middle, grab the ends and leverage it against your thumbs? Trees are just really big pencils. By loading the grain of the tree, it preserves more of its strength and prevents the tree from breaking when we don’t want it to.

In terms of the equipment, know that there are limits there as well. The breaking strength is going to be different for the different pieces of kit.

Diameter of rope: Typically, the larger the rope, the stronger – but not always. Some pulleys allow for larger ropes to be used than others. Putting too large a rope in a small sheave will reduce the strength of the rope. Bend ratios matter, and if too much force is applied, it can cause a failure. Maybe not a right-then-and-there failure, but you’ll notice more wear and tear on the equipment as a result.

Conclusion

The point of all this is, know what you’re rigging and with what.

As much as humanly possible, I want my rope to be the weakest link. I’m designing a series of properly placed points to allow for the tree to be helpful, to use (or not use) friction accordingly. Most important, I continue to learn and be intentional about what I’m trying to do in any given situation. It’s not simply to put ropes, blocks and rings in places because it’ll get more likes on Instagram, but to be thoughtful about what to deploy and how it affects the overall performance of the task at hand.

I hope this sparks some thoughts with you, as the reader, to gain more knowledge, be curious and work smart and hard. We don’t want to hear the line, “You are the weakest link – goodbye.” It was a fun show, but not a fun way to operate in trees. Climb high, cut small (unless you can go big) and go home. There will be more trees to play in tomorrow. Use your knowledge wisely.

Jeff Inman Jr., CTSP, is an ISA Certified Arborist, is ISA Tree Risk Assessment Qualified and is an ISA Tree Worker Climber Specialist. He is risk manager with Truetimber Arborists Inc., an accredited, 20-year TCIA member company based in Richmond, Virginia, and Truetimber Academy director.